Lenin in Zurich – information board Spiegelgasse 14

Undeniably a figure of world history – that is how the mayor of Zurich, Emil Klöti, justified the inscription on the house front at Spiegelgasse 14 in 1928. The Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (1870–1924) and his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869–1939) lived there as lodgers for a little over a year before leaving Zurich for Russia on 9 April 1917.

And yet hardly anyone would have attributed world-historical status to Lenin at the time. Indeed, little is known about the revolutionary’s activities and everyday life in Zurich. Apart from the Swiss historian Willi Gautschi, it was above all the Russian dissident and Nobel Prize winner for literature Alexander Solzhenitsyn who, based on Gautschi’s work, investigated Lenin’s stay in Zurich after his expulsion from the Soviet Union. But who was the Russian who went down in history under the pseudonym “Lenin”, as he has been referred to since 1900? He remains a controversial figure to this day. Some see him as the strong-willed, determined and uncompromising mastermind and organiser of the October Revolution, while for others, he perverted the theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to create the foundations for a regime of terror.

The problem of trying to draw up a critical evaluation lies in the discrepancy between Lenin’s simple, if not tranquil everyday life in Zurich and his subsequent importance on the world political stage after his seizure of power in Russia. In his book “Lenin as an Emigrant in Switzerland”, Gautschi, who is the historian most familiar with the subject, talks about an “intellectual explosive” that was “made in Switzerland” and “detonated in the October Revolution”. At the same time, he quotes Fritz Platten, who stated when referring to the Russian revolutionaries gathered in Zurich in 1917, that no one would have predicted that "these poor wretches [...] could become leaders and rulers of a nation of a hundred-and-thirty million people". It is very difficult to explain history in retrospect. At the same time, it is a matter of evaluating the historical role of “great” individuals and the significance of ideologies. Did the path from the writings produced in Zurich and Lenin’s personality lead directly to the Red Terror, or did Lenin in fact assert himself as the leader of the Russian Revolution only after his return, one step at a time, in the course of a civil war fought brutally on both sides? Was the tyranny that involved the establishment of a “proletarian dictatorship” and the creation of camps for countless political prisoners, especially under Stalinism, the logical consequence of Lenin’s ideological preoccupation in Switzerland, or would it be true to say that the chaos of the First World War and the division and paralysis of the Russian government in 1917 played at least as important a role in the radicalisation? It is undisputed that Lenin ruthlessly seized power with single-mindedness and a sense of mission, before a little later advocating a relaxation of economic conditions under the “New Economic Policy” (NEP), along with a wider acceptance of culture. In view of these very different, if not contradictory, factors, coming to any conclusion about Lenin’s stay in Zurich is inevitably a difficult task. But what can be said about Lenin’s years in exile in Switzerland, and especially in Zurich?

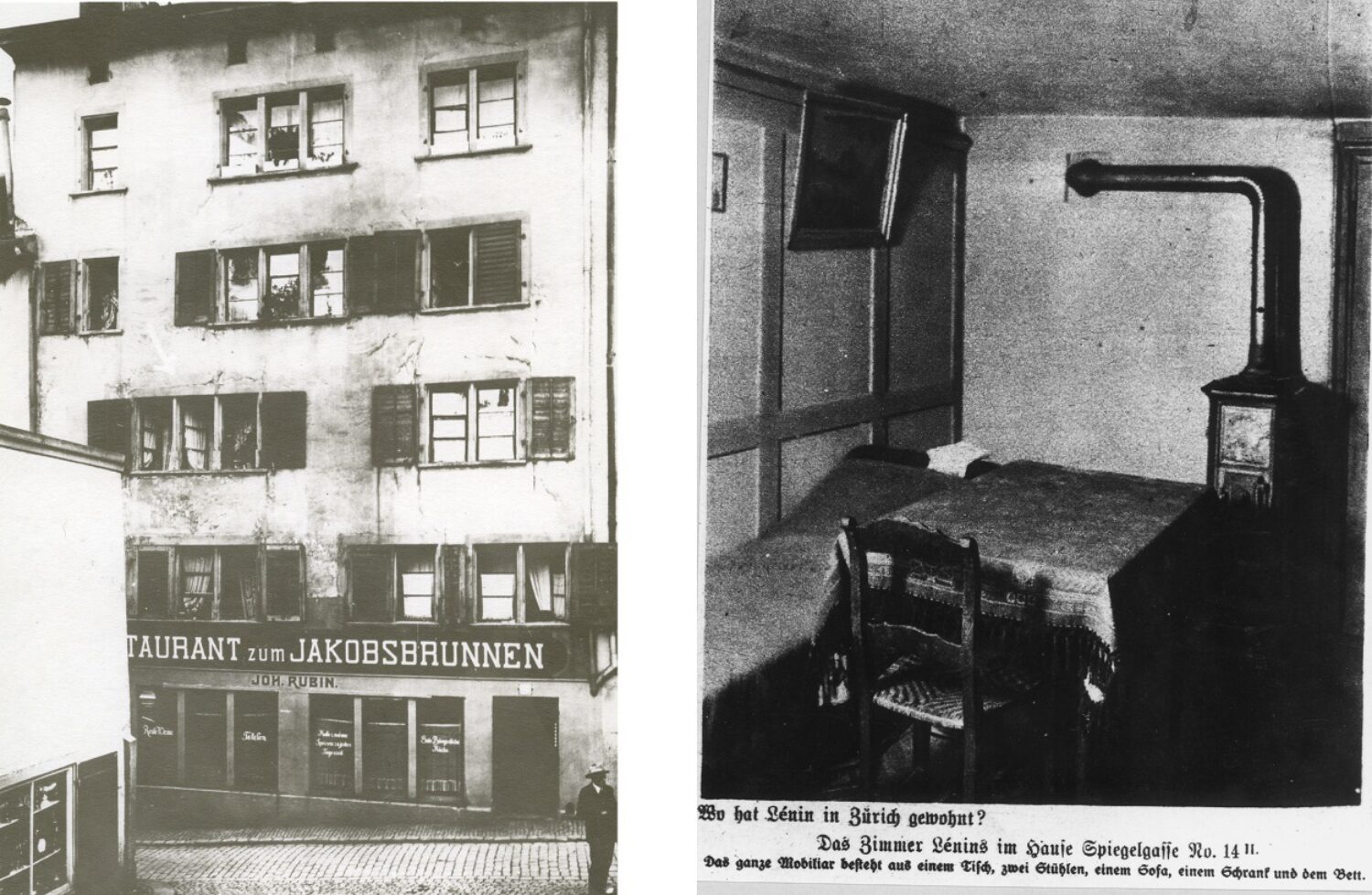

Many Russian socialists and social democrats lived in exile in Switzerland because they were able to maintain contact with like-minded people here. Not least, many women studied at the University of Zurich. In order to visit them, Ulyanov came to Zurich briefly for the first time in 1895. After Lenin had published his concept of a single ruling revolutionary Marxist party in “What is to be done?” in 1902, he had to go abroad again following the failed Russian revolution of 1905/6. He settled in neutral Switzerland after the outbreak of the First World War. After spending time in Geneva and Bern, he moved to Zurich with his wife in February 1916, initially to Geigergasse near Schifflände, and a little later to Spiegelgasse. There, a young socialist boy helped the couple to find accommodation with his uncle, the shoemaker Titus Kammerer, on the second floor of the “zum Jakobsbrunnen” house.

Lenin actually wanted a room with a simple working-class family, but given his financial means, he was probably quite satisfied with the modest double room in a craftsman’s home. The annual rent of just under 300 francs must be set against the average worker’s wage of 3-4,000 francs. The rooms were small and conditions in the flat were cramped. Alongside the five members of the Kammerer family, other lodgers lived there too: an Italian, some Austrian actors with a ginger cat, and the wife of a German soldier with her children. Lenin’s room faced the backyard, where a sausage factory spread unpleasant odours. Food was often prepared on a small paraffin stove. The very narrow buildings on Spiegelgasse contributed to a rather problematic hygenic situation. The houses opposite Spiegelgasse 14 were demolished in 1938/39 as part of an urban redevelopment plan, and were replaced by the present green space. Lenin’s house, on the other hand, was left in place until it became so dilapidated that it had to be demolished and rebuilt in 1971/73.

Picture: Urban redevelopment: demolition of the Spiegel-/Leuengasse houses in 1938 and creation of a square. © Architectural History Archive of the City of Zurich

The reasons for Lenin’s move to Zurich are probably mainly to be found in Bern, which Krupskaja perceived as a “petty-bourgeois democratic cage” and where Lenin’s ideas met with little enthusiasm. In Zurich, he hoped to join the Russian emigrant circles that met in the German workers’ association “Eintracht Zürich”, whilst also aspiring to acquire greater influence on the revolutionary youth. In his residence permit application, Lenin described himself as a “political emigrant since the 1905 revolution” without any assets, who lived from his literary and journalistic work. Lenin had two important contacts in Zurich in Willi Münzenberg and Fritz Platten; he supplemented his modest income with occasional lectures. Above all, he worked tirelessly on his work “Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism”, and spent time in libraries. Every day, he studied newspapers in the nearby Eintracht union building (now the theatre and guild house on Neumarkt). Occasional hikes with the workers’ association in the area surrounding Zurich and a stay at a health resort in the Flumserberge brought some variety to his everyday life.

The Ulyanov-Krupskaya couple found themselves in a historic setting when they moved into their flat on Spiegelgasse: in the neighbouring house at no. 12, the writer and natural scientist Georg Büchner died of typhoid fever in 1837 at the age of 23; he had fled Hesse in 1835 on account of his subversive ideas. His preoccupation with the French Revolution (“Danton’s Death”) linked him to the Russian revolutionaries, who repeatedly referred to the events in Paris. The famous priest and philosopher Johann Caspar Lavater was born on Napfplatz in 1741, and the confectioner and actor Emil Hegetschweiler, co-founder of the anti-fascist “Cabaret Cornichon” in 1934, ran a bakery there. Finally, at Spiegelgasse 1, Hugo Ball opened the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, a popular meeting place for avant-garde artists in exile from all over Europe, and the birthplace of Dadaism. Whether Lenin ever visited the cabaret is highly questionable.

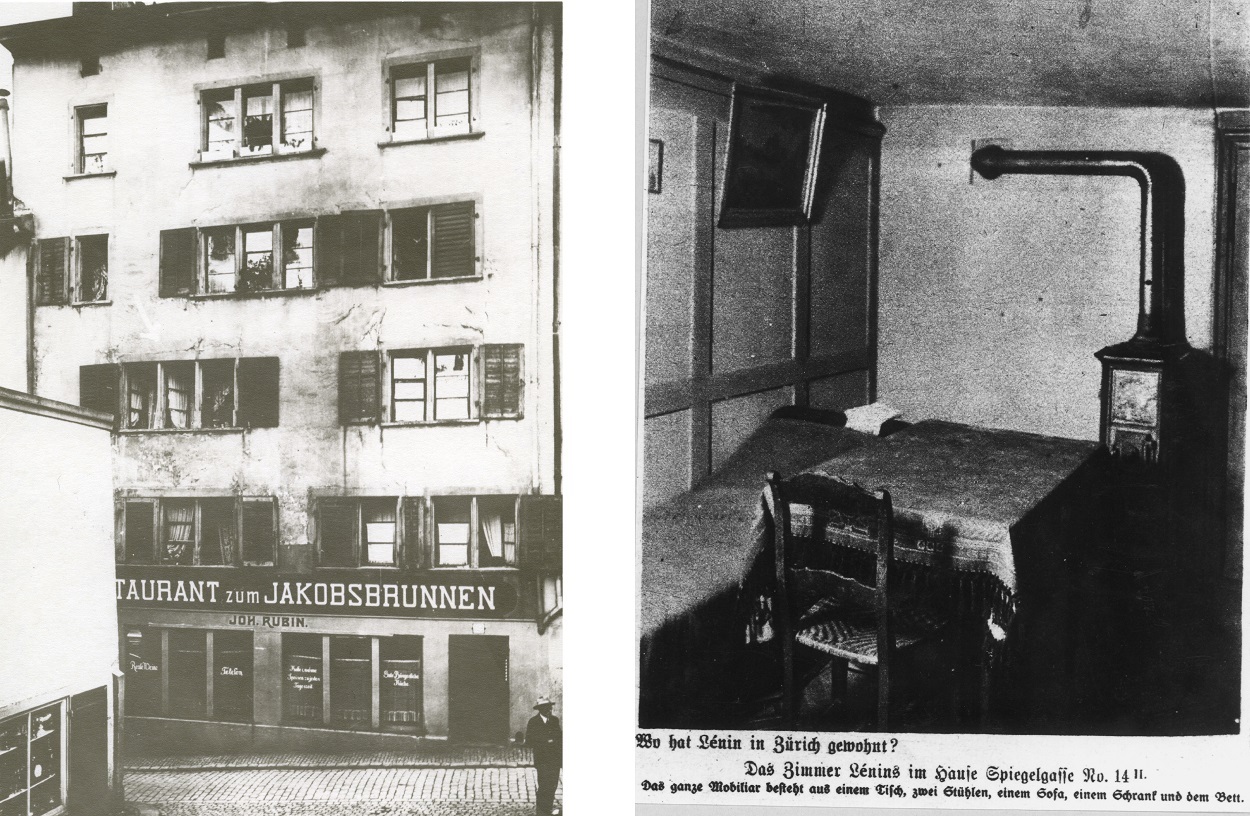

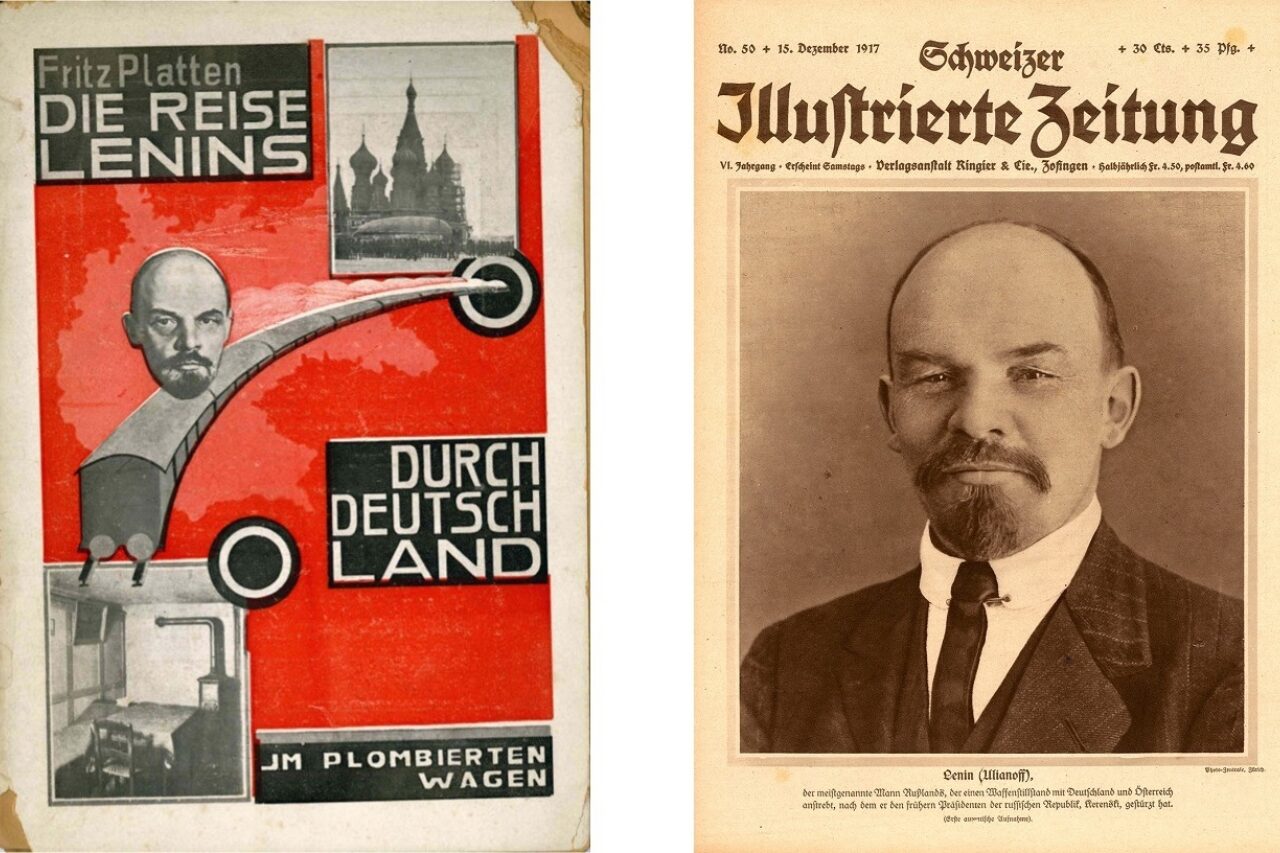

Picture left: Lenin’s journey to Russia: cover of the book published by Fritz Platten in 1924; Picture right: Lenin as a figure of world history: cover of the Schweizer Illustrierte Zeitung dated 15 December 1917.

Lenin’s patient courting of the Swiss socialists ended with the fall of the Tsar in the February Revolution of 1917. His energy was now focused entirely on finding a way back to Russia to lead the Bolsheviks in Petrograd (as St Petersburg was called from 1914 to 1924 before it was renamed Leningrad) in their struggle against the new government. The German government was interested in encouraging Lenin’s return because he was strongly in favour of ending the war. Lenin, in turn, did not want to miss this favourable moment for socialist revolution and was therefore willing to take the risk of travelling through German territory. Under constitutional law, this meant he committed treason, which is why he obtained special conditions from the Germans. With the active assistance of Fritz Platten, he and 30 other compatriots boarded a supposedly sealed, but probably simply ex-territorial, railway carriage in Zurich on 9 April 1917, which took them through Germany to Stockholm, from where they continued to the Russian border. A little later, Lenin became a historical figure of international significance. Fritz Platten, on the other hand, had to turn back at the Russian border. After the October Revolution, he travelled to Soviet Russia again and again: he allegedly saved Lenin's life in 1918 during an assassination attempt, he founded several agricultural cooperatives after 1923, and he settled permanently in Russia with his third wife in 1926. Arrested a good ten years later during the Stalinist purges, Platten was shot in a camp in northern Russia in 1942, on Lenin’s birthday of all days.

Cover picture left: In the heart of the old town: the “zum Jakobsbrunnen” house and restaurant in the early 20th century. © Architectural History Archive of the City of Zurich. Picture right: A modest home: Lenin’s room in around 1924; photo by Wilhelm Gallas, © Architectural History Archive of the City of Zurich